Introduction

Introduction¶

It has been shown that Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) at Ultra High Field (UHF, 7 tesla and above) results in a better Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and thus allows for a better image resolution and/or shorter scan time, which is of interest for diagnostic purpose and clinical workflow. These benefits are mainly due to the fact that the measured MR signal is directly proportional to the square value of the main magnetic field strength \(B_0\):

With:

\(\gamma\): gyromagnetic ratio of the proton (\(2.675 \times 10^8 s^{-1} T^{-1}\))

\(\rho_0\): spin density (number of protons per unit volume in \(m^{-3}\))

\(T\): Temperature (\(K\))

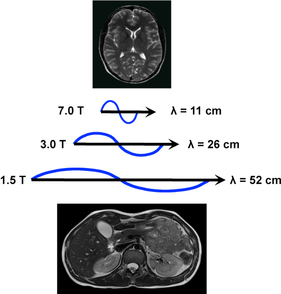

These improvements come along with a decrease of the wavelength of the radio-frequency field \(B_1\) required to flip the spins, as the wavelength \(\lambda\) relates to \(B_0\) as follows:

With \(\epsilon_r\) being the permittivity of the propagation medium.

At UHF, it thus becomes hard to get a homogeneous flip angle over a body-sized region of interest. For example, at 7T the RF wavelength in the human body is approximately 11 cm, which is on the order of the field-of-view used to image with MRI.

As the measured MR signal is directly proportional to the flip angle (for the simple gradient echo experiment, assuming a starting condition with fully relaxed spins), this results in an inhomogeneous intensity across the images acquired at UHF.

The RF wavelength shortens as the \(B_0\) field increases.

Source: Questions and Answers in MRI: Dielectric effect

Moreover, imaging at UHF often requires the use of coils composed of multiple transmit elements positioned close to imaged region (e.g., head coils, spine coils, knee coils). The use of multiple elements induces constructive and destructive RF-interferences within the patient’s tissues, potentially resulting in inhomogeneous intensities across the final MR images and high energy deposition at specific spatial locations.

To overcome these challenges and produce homogeneous RF fields, the monitoring of the phase and magnitude of each transmit elements along with RF pulse design methods have been developed during the past decades. This process is usually referred to as \(B_1^+\) shimming or RF-shimming.

This Jupyter book aims to present the basis of RF-shimming and to show examples of algorithms that can be used to homogenize the \(B_1^+\) field.